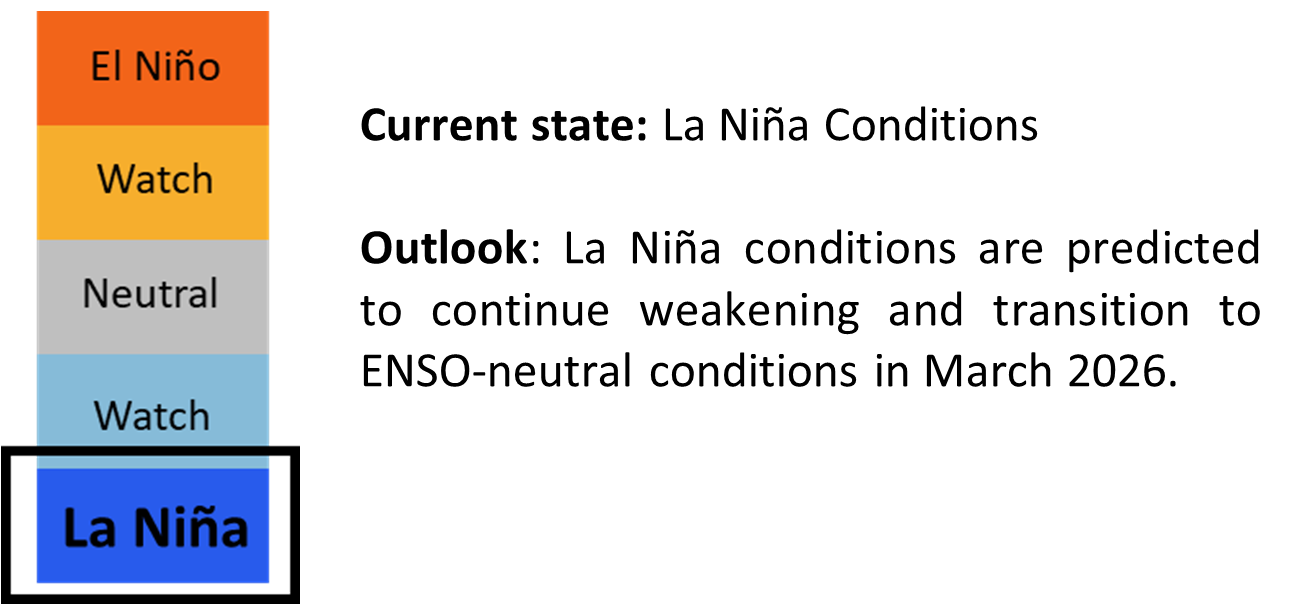

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) monitoring system state is “La Niña Conditions”. The Nino3.4 index shows the presence of La Niña conditions. Key atmospheric indicators (cloudiness and trade winds in the central Pacific) indicate that La Niña conditions have already begun to weaken, with subsurface ocean temperatures also supporting a transition away from La Niña conditions. The Nino3.4 index was -0.96°C for January 2025 and -1.07°C for the November 2025 – January 2026 three-month average.

La Niña conditions are predicted to weaken in February 2026 and transition to ENSO-neutral conditions in March 2026. Models predict the ENSO-neutral conditions to persist at least until May 2026, with either ENSO-neutral continuing or El Niño conditions developing in June-July 2026.

Short note on the Indian Ocean Dipole: The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is currently neutral. Models predict the IOD to remain neutral until at least April 2026.

Further Information on ENSO

ENSO conditions are monitored by analysing Pacific sea surface temperatures (SSTs), low level winds, cloudiness (using outgoing longwave radiation), and sub-surface temperatures. Special attention is given to SSTs, as they are one of the key indicators used to monitor ENSO. Here, three different datasets are used: HadISST, ERSSTv5, and COBE datasets. As globally, SSTs have gradually warmed over the last century under the influence of climate change, the SST values over the Nino3.4 will increasingly be magnified with time, and hence appear warmer than they should be. Therefore, this background trend is removed from the SST datasets (Turkington, Timbal, & Rahmat, 2018), before calculating SST anomalies using the climatology period 1976-2014. So far, there has been no noticeable background trend in the low-level winds or cloudiness.

El Niño (La Niña) conditions are associated with warmer (colder) SSTs in the central and eastern Pacific. The threshold for an El Niño (La Niña) in the Nino3.4 region is above 0.65°C (below -0.65°C). El Niño (La Niña) conditions also correspond to an increase (decrease) in cloudiness around or to the east of the international dateline (180°), with a decrease (increase) in cloudiness in the west. There is also a decrease (increase) in the trade winds in the eastern Pacific. Sub-surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific should also be warmer (colder) than average, to sustain the El Niño (La Niña) conditions.

For ENSO outlooks, information from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and international climate centres are assessed. The centres include the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) USA, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) Australia, as well as information from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) which consolidates model outputs from other centres around the world. Each centre uses different criteria, including different SST thresholds. Therefore, variations between centres on the current ENSO state should be expected, especially when conditions are borderline.

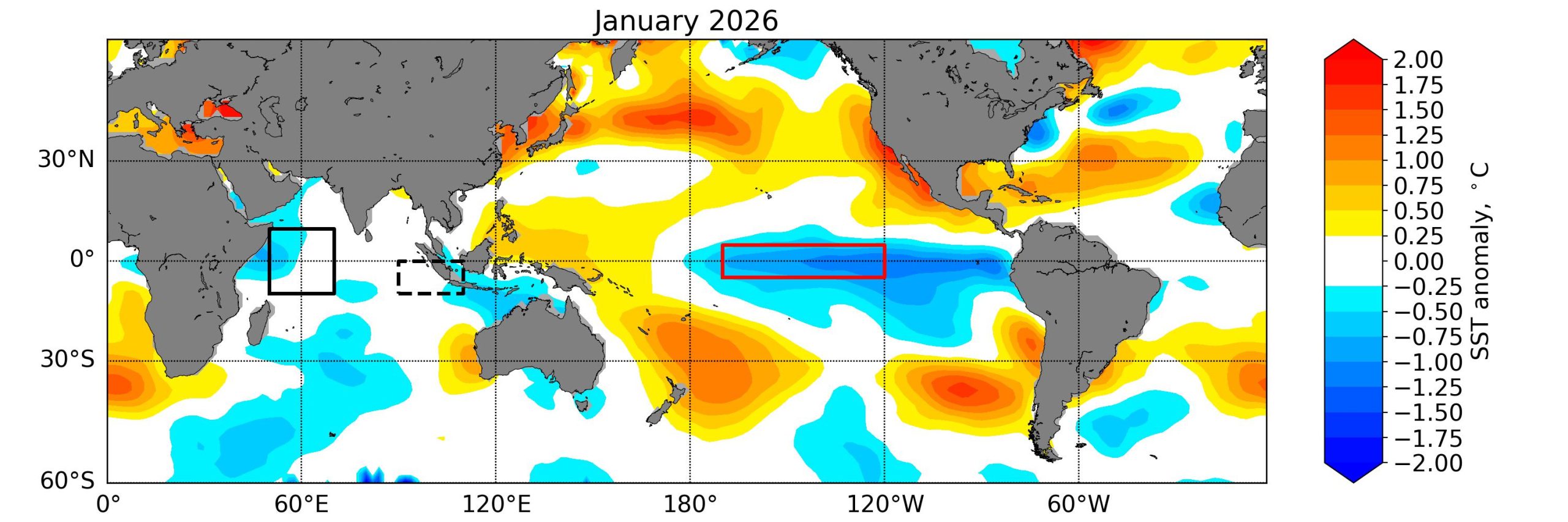

The sea surface temperatures (SSTs) over the tropical Pacific in January 2026 were below average in the central and eastern portions of the region and above average in the west, indicative of La Niña conditions (Figure 1). The coolest (negative) anomalies were in the eastern tropical Pacific including the Nino3.4 region (red box). Across the Indian Ocean, the equatorial region was near-average in the eastern parts of the region (including the dashed black box). The equatorial region in western part (including the sold black box) was likely also near-average, with small anomalies whose sign differs in different datasets (not shown). This dipole pattern indicates the IOD remained neutral in January 2025.

Figure 1: Detrended SST anomalies for January 2026 with respect to 1976-2014 climatology using ERSST v5 data. Red (blue) shades show regions of relative warming (cooling). The tropical Pacific Ocean Nino3.4 Region is outlined in red. The Indian Ocean Dipole index is the difference between average SST anomalies over the western Indian Ocean (black solid box) and the eastern Indian Ocean (black dotted box).

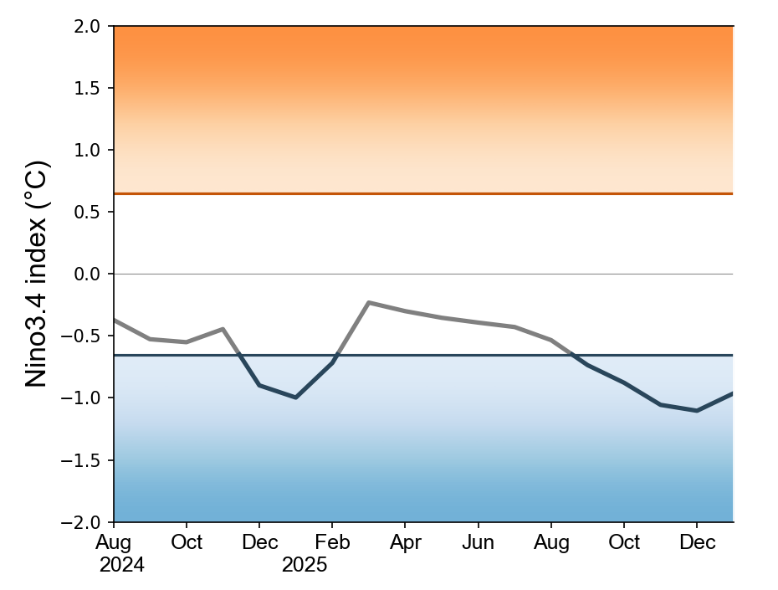

Looking at the Nino3.4 index in Figure 2, the 1-month Nino3.4 index first passed the La Niña threshold in December 2024 and returned to ENSO neutral in March 2025. The Nino3.4 index was then negative, but within the ENSO neutral range, until September 2025, when it passed the La Niña threshold again. For La Niña conditions to be present, 1-month of cold SST anomalies (observed or forecast) should persist for at least four months below the threshold, with at least one of the months observed; along with supporting atmospheric observations.

Figure 2: The Nino3.4 index using the 1-month SST anomalies. Warm anomalies (≥ +0.65; brown) correspond to El Niño conditions while cold anomalies (≤ -0.65; blue) correspond to La Niña conditions; otherwise neutral (> -0.65 and < +0.65; grey).

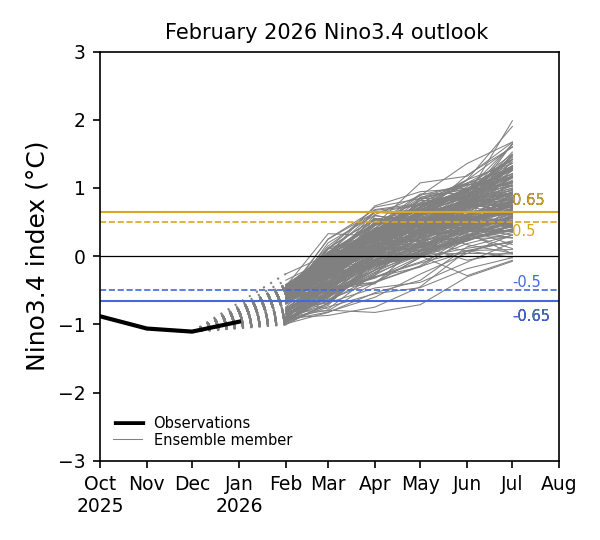

Model outlooks from Copernicus C3S (Figure 3), based on the Nino3.4 SST index, show that models predict La Niña conditions to continue weakening, with a return to ENSO-neutral conditions very likely from March 2026 onwards. In July, models predict either ENSO neutral or El Niño conditions, although there is considerable uncertainty in the long-term forecasts at this time of the year.

Figure 3: Forecasts of Nino3.4 index’s strength until July 2026 from various seasonal prediction models from international climate centres (grey lines). The blue and yellow lines note the La Niña and El Niño thresholds, respectively, used by various centres.

Historical ENSO Variability

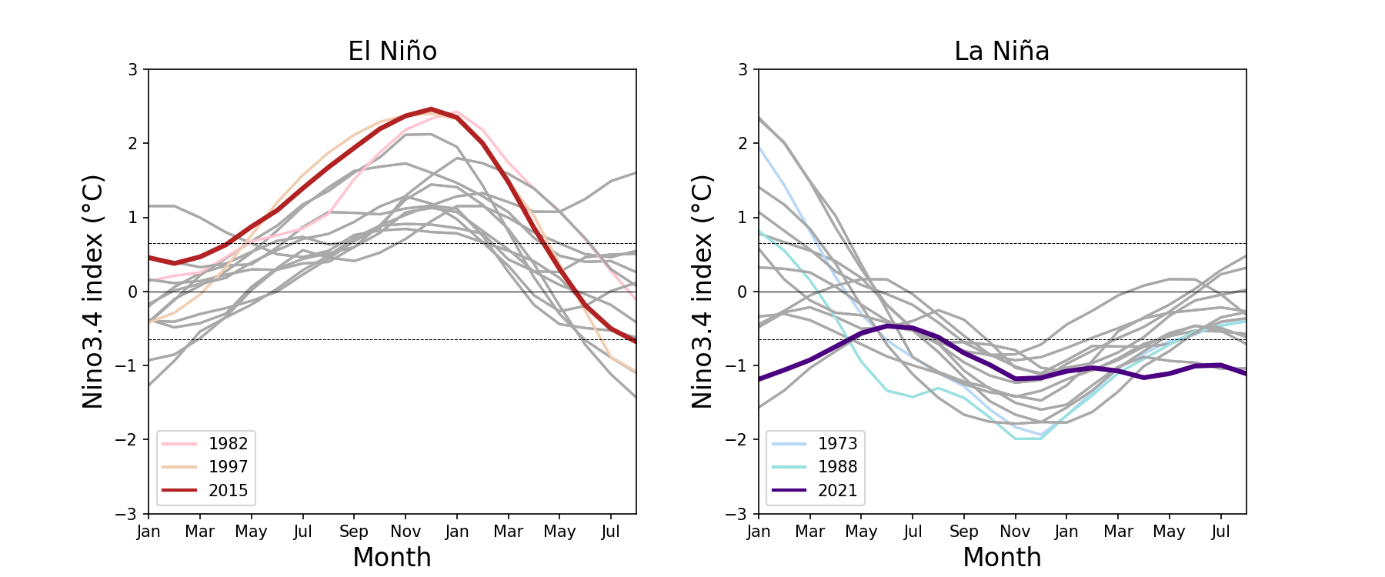

To classify a historical El Niño event, the 3-month average Nino3.4 value must be above 0.65°C for 5 or more consecutive months. For La Niña events, the threshold is -0.65°C. Otherwise it is considered neutral. ENSO events with a peak value above 1.5°C (El Niño) or below -1.5°C (La Niña) are considered strong. Otherwise, the events are considered weak to moderate in strength. The following figure (Figure 4) shows the development of the Nino3.4 index for the most recent El Niño and La Niña events in comparison to other El Niño/La Niña events.

Figure 4: Three-month Nino3.4 index development and retreat of different El Niño (left)/La Niña (right) events since the 1960s. Recent El Niño and La Niña events are in red and purple, respectively.

Impact of El Niño/La Niña on Southeast Asia

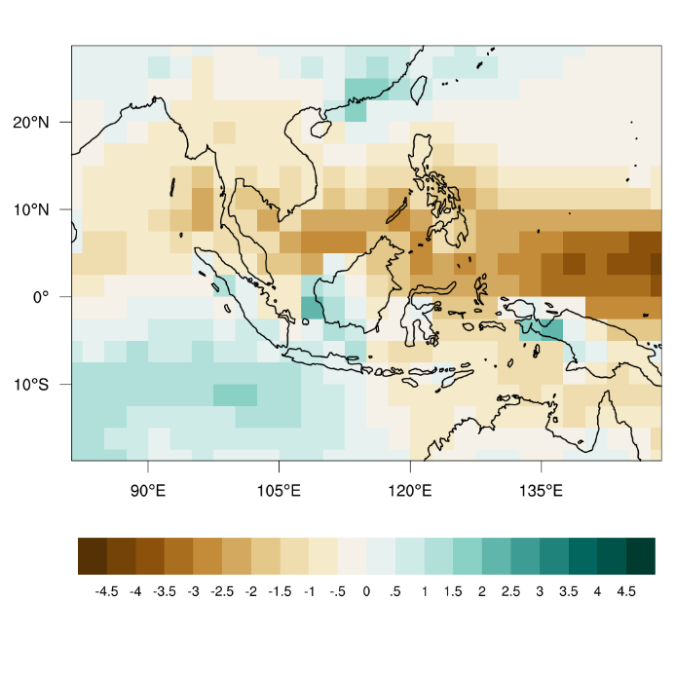

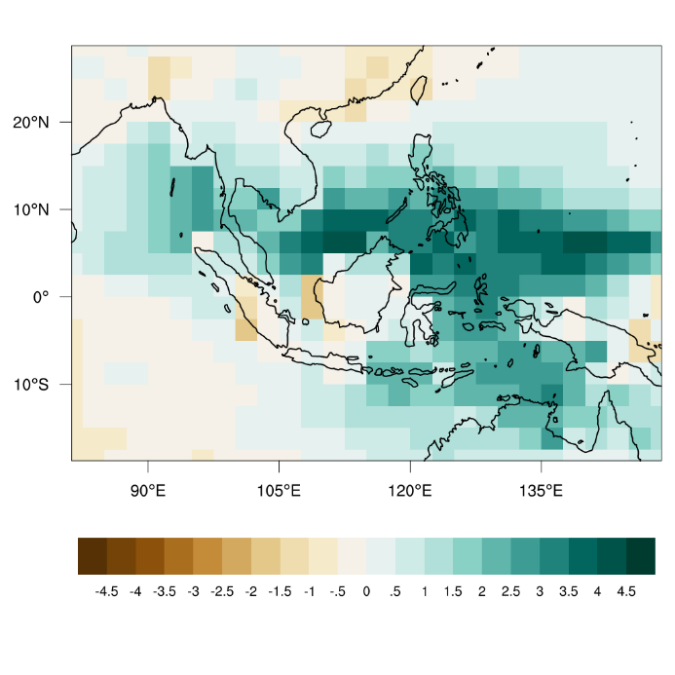

The typical impact of La Niña on Southeast Asia is wetter-than-average rainfall conditions, including for much of the Maritime Continent during March – May (Figure 5, right). The opposite conditions for rainfall (and consequently temperature) are observed during El Niño years (Figure 5, left).

The impact on the region’s rainfall and temperature from ENSO events is more significantly felt during strong or moderate-intensity events. Also, no two El Niño events or two La Niña events are exactly alike in terms of their impact on the region.

Figure 5: March to May (MAM) season rainfall anomaly composites (mm/day) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. Brown (green) shades show regions of drier (wetter) conditions. Note that this anomaly composite was generated using a limited number of El Niño and La Niña occurrences between 1979 and 2017 and therefore should be interpreted with caution (data: NOAA CPC CAMS_OPI).

References

Turkington, T., Timbal, B., & Rahmat, R. (2018). The impact of global warming on sea surface temperature based El Nino Southern Oscillation monitoring indices. International Journal of Climatology, 39(2).

El Niño/La Niña

-

For El Niño/La Niña updates, information provided by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and various international climate centres are assessed. The centres include the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) USA, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) Australia, as well as information from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) which consolidates model outputs from various other centres around the world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is El Niño/La Niña and how do they affect weather in South East Asia?

The El Niño phenomenon is a non-regular occurrence in the tropical pacific region where warmer waters develop over the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean along the coast of South America. In South East Asia, this brings drier weather and increases the risk of forest fires and smoke haze. The La Niña phenomenon is the reverse of the El Niño where cooler waters develop over the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean along the coast of South America.

In South East Asia, higher than normal rainfall tends to occur during a La Niña episode which may result in an increased occurrence of floods.

Cross section of El Niño, neutral and La Niña conditions across the Tropical Pacific Ocean. (Image credit: NOAA)

The correlation between El Niño/La Niña and its associated weather impacts on South East Asia differ from one place to another and for different seasons.

Distribution of precipitation anomalies over South East Asia (Jun – Oct) for El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) years. (Image credit: IRI Climate)

The image above shows the precipitation anomalies averaged over the El Niño and La Niña years. For instance, the impact of El Niño is typically stronger over the southern and eastern part of South East Asia during the months of Jun – Oct.